On day 7 of the 16 Days of Action, our Service Manager Claudene Centinoglu breaks down the reality of child removal for women and the need for early support for mothers.

This year, White Ribbon Day calls for a transformative approach—to #ChangeTheStory. This means unlearning and relearning our attitudes and behaviours towards women.

It means we can all be agents of change in shifting narratives, reshaping and redefining how we view and treat each other.

Understanding the Reality:

Before we delve into how we can #ChangeTheStory, it is crucial to acknowledge the stark realities faced by women today. The statistics speak volumes:

• Nearly 1 in 4 girls in mixed-sex schools has experienced unwanted sexual touching. (EVAW)

• 6 in 10 women have felt harassed in the gym by a man. (The Gym-timidation Report)

• 30% of women have encountered workplace harassment, with 81% reporting harassment by men. (Government Equalities Office)

• 7 million women experienced domestic abuse in the year ending March 2022. (ONS)

My name is Claudene and I have worked alongside women for a good few years in both a paid and voluntary capacity. I have been fortunate enough to witness exhilarating highs and transformations in women’s lives; however with the good does indeed come the bad – spaces where hope feels lost and transformations feel unreachable. This can feel especially pertinent when women are facing child removal or are interacting with the child protection arena.

Now, before this blog explores the theme of women facing child removal, I want to say I fully understand the role that child protection plays in keeping some of society’s most vulnerable children safe and free from harm. However, I also understand, and truly believe this system is ready for transformative and progressive change. Something I remain fully committed to when working alongside colleagues from statutory services.

Our Local Picture:

In the North-east of England, austerity measures introduced by the UK Government over the last decade have had a greater impact in the most deprived areas of the country, including the North-east, due to disproportionately higher cuts and the impact on spending power. Since 2009 there has been a 77% increase in the number of children being placed in care. (Northeast ADCS, 2021).

So, what does that mean for frontline services supporting women who have had children removed? It can mean working with women who may have lost hope, who struggle to trust kindness and who look for support in places that often offer a help that is siloed – seeking a help that is desperately trying to paper over the ambiguous loss and grief of child removal. I recently received a referral for a woman into a service that I manage – and it reads like two different women, a before and after version of the woman needing support. In the “Other Information” part of the referral form – a date stared back April 2021 “children permanently removed from mum’s care”. A mum with children in her care, a mum without children in her care, permanently – a stark difference to navigate when shaping support to meet her needs.

The damaging effects of child removal on both the child and the birth mum have already been well documented by social researchers. Known issues include increased risk of suicide attempts and completions among mothers who have had their children removed (Wall-Wieler, 2018).

Researchers at Glasgow University reported that a significant increase in drug related deaths in Scotland in 2020 could be traced back to mothers who had had their child removed from their care (Tweed et al. 2020). MMBRACE have identified child removal via state intervention as the leading correlating factor in suicide in the first 12-months post birth (MBRRACE UK, 2022).

The impact on children is also far reaching; there is an increased risk of developing mental health issues among children (Trivedi, 2019) and increased risk of experiencing homelessness or prison later in life (MacAlister, 2022).

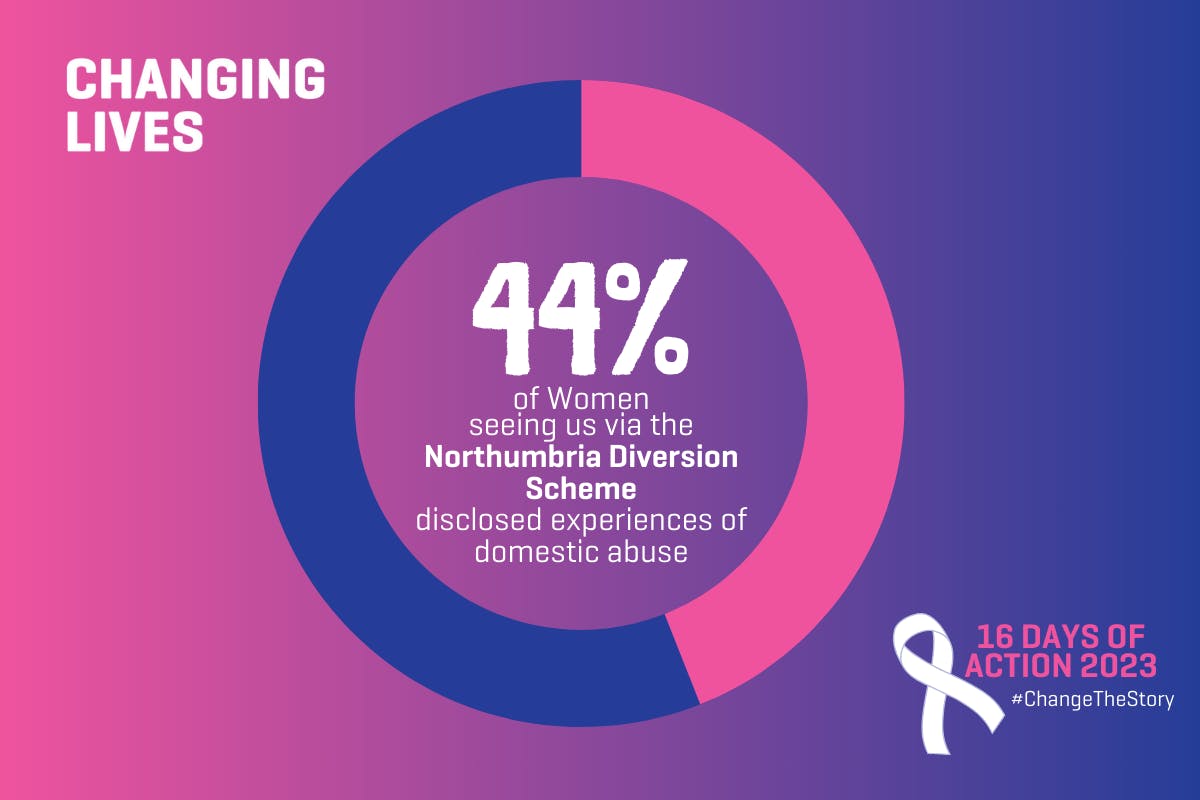

Child Removal and Domestic Abuse:

42.6% of incidents involving serious harm to children in 2020 involved Domestic Abuse and Violence. Practical innovations and the Domestic Abuse Act (2021) have attempted to fortify protections for children. However, research suggests there are persistently problematic practice features. Responses and referrals often fail to differentiate between types of abuse and levels of risk, depriving decision makers of important tools. Mums, often the focus of harm, become subject to Child Protection investigations and judgements of ‘failing to protect’, potentially resulting in the removal of their children. Other victims of abuse may receive no intervention. Children and parents who have been separated receive little trauma-informed support. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting separation increases risks.

Removing children from their mum, at times breaking up sibling groups in the process. By blaming the distressed victim for “failing to protect” is the ultimate form of victim blaming. It has deeply sexist echoes of the way women are regularly held to account by asking them to change their behaviours, clothes and where they walk, so they 'do not get raped', which is synonymous with saying they have power to prevent that situation.

A question I often reflect on with the teams I work with is “Can we effectively protect children if we view the prevention of harm from domestic abuse as the victim’s job?” More often, this reflection highlights the failure to put the responsibility in the right place – with the perpetrator.

We know that domestic abuse perpetrators regularly break court orders put in place to offer protection to victims, with virtual ramifications. And so, the logic of children’s services is at times, fatally flawed: when even the courts cannot restrain a violent criminal, what hope has any victim? How can a woman be required to pack up with her children and leave her home when the refuge and support services to provide sanctuary for families no longer exist in so many parts of the country?

The Power of Early Help:

#ChangeTheStory

How do you motivate a mum when the cliff edge is fast approaching? Or worse still, the freefall is happening – the children have been removed and everything has changed.

I believe that when we meet mum at earlier opportunities, we do not wait for the crisis point to arrive. We provide mum, with skills, space and time to navigate the problem she is enduring in real time.

We give her the tools to build resilience, so that if it does happen again, as we know most problems do not just go away at the first attempt we try to tackle them, she has the learning to respond accordingly and with confidence. Supporting people to help themselves.

We create spaces at every opportunity for mum to say how she is struggling and what support looks like on her terms. So often, at crisis points, common sense can go out the window with a fight or flight response activated - we accelerate the need to protect so are often missing out mum’s needs at this crisis point. We need to give power to earlier conversations – a confidence in being proactive, not reactive.

The role of early help in supporting vulnerable families:

- Early help builds a sense of community and belonging, not a state intervened approach.

- Early in the life of the problem - whatever the age of the child or young person.

- Early to respond when problems emerge or re-emerge.

- Help to prevent concerns getting worse and avoid the need for statutory intervention.

- Support in school, home and community through a graduated approach

- Early help is driven by a cross multi-agency approach – representation from public health, social care and the third sector works in a way that is collaborative with the family at the heart.

Right Conversations, Right People, Right Time

If any of the issues we’ve raised affect you or someone you know and you need support, you can get in touch with us on central.office@changing-lives.org.uk or call us on 01912738891. You can find out more about the type of support we offer here.